“But the old tactician has got a plan.”

There is no way in this (or any other) universe that I would be writing a film Substack without the illumination and guidance I was lucky enough to receive from David Enelow, the greatest teacher in the world.

As will undoubtedly shock my readers, I believed I was an excellent English student entering my Junior year of high school. Mr. Enelow quickly and directly disabused me of that notion. (I was good; I was not great.) And then he set me on a course to becoming an excellent English student not just in my mind, but in reality.

Our primary vessel, as it were, was the Odyssey. It was the first and remains the signature text of that course. (As former students will confirm, that’s the text that features most prominently in all my very Enelow-derivative guides to writing essays.) And look: there were definitely moments when I felt lost reading that text; more than once, I felt petrified in a class discussion, woefully unready to say anything meaningful or correct, and desperate not to be called on.

But I did not like the idea of letting Mr. Enelow down. I wanted to show that I could succeed, could meet his expectations. So I put in the work, and slogged through that text. And by the time we turned in our final assignment, I felt confident in my understanding of the poem.

By the time I read it again for a college course, I felt like an Odyssey expert—all that high school work had paid off. In fact, I felt so comfortable with it that I wrote a fifteen-page imitation piece called the Oddity, featuring my best go at Homer’s writing voice to chronicle an epic tale of me trying to get to class to take an exam.

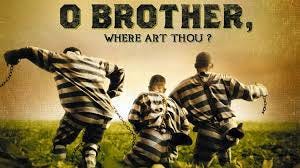

I mention my history with the Odyssey because it is that very history that led me not to like O Brother, Where Art Thou? at all when I first saw it.

“Pete, the personal rancor reflected in your remark I don’t intend to dignify with comment.”

I believed I was going to see the Odyssey set in 1930’s Mississippi. That’s not what I got. And so, as is cliché for English teachers everywhere, I was pretentiously indignant that “the movie wasn’t as good as the book.” And it was more than that. I felt betrayed, because, in my expert opinion, it wasn’t even close.

I soon saw the movie for a second time, and it didn’t take long for me to see how dumb that critique was. First of all, there are indeed tons of nods to the Odyssey. You’ve got a protagonist named Ulysses; a blind prophet; sirens; Penelope (Penny), the wife who provides consistent challenges; a suitor; and my favorite, the Cyclopean Big Dan Teague, whose catch of the Confederate flag is about as perfect as allusions get. But secondly, and more importantly, O Brother, Where Art Thou?’s liberal adherence to the Odyssey is a strength, not a weakness.

(Historical footnote: It did take me a long time to discover another reason why crushing O Brother for being insufficiently Odyssey-adjacent was particularly dumb: The Coen brothers did not conceive of this film as an updated Odyssey; they envisioned it more as a take on The Wizard of Oz. It wasn’t until much later they decided to “just say this is the Odyssey.” What makes that funnier is that the Coen brothers had never even read the Odyssey. Tim Blake Nelson had read it twice, and would thus not only play Delmar but serve as an informal script advisor.)

The Coen brothers specialize in mixing tones and genres. (As I’ve written before, Fargo provides perhaps the best example of this filmmaking nimbleness.) And while O Brother doesn’t switch tones often or radically, it’s definitely a mythological mélange, including nods to (of course) Greek mythology, but also Southern mythology, Christian mythology, and even Blues mythology. (Anyone remotely familiar with the legend of Robert Johnson can’t help but smile when they see Tommy standing at the crossroads, a smile that continues as he relays his origin story.)

Synthesizing all these mythologies while presenting a story that moves organically and efficiently is a high-degree-of-difficulty endeavor. But, as usual, the Coen brothers make the difficult look easy.

“She counted to three. Goddammit! She counted to three.”

Once I fell for O Brother, I fell hard; and it quickly found its way into my Film Lit class. Like The Matrix, O Brother existed in Film Lit’s Wild West Era. As an early-semester introduction to structural elements and well-executed story fundamentals, it worked well.

In many ways, O Brother’s reliable and confident application of the Rule of 3 makes it a Film Lit teacher’s dream come true. (While I’m at it, the college-level vocabulary makes it a literature teacher’s dream come true. Some of the lines are just gloriously bombastic.) Over and over, the Coen brothers show the simple effectiveness of Establish, Confirm, Reverse. Here are just a few examples:

Everett makes it on to the train. Delmar makes it on to the train. Pete falls and drags Everett and Delmar with him. (Note: the Coen brothers revel in close-ups of quirky facial expressions, and the shot of Everett as he’s about to be dragged from the train is one of my all-time favorites.)

Pete votes that he should be named “leader of this outfit.” Everett votes that he should be named “leader of this outfit.” Delmar—who’s so sweet that butterflies flock to him—looks at both of them and says, “All right. I’m with you fellers.” (Another quick note on Delmar’s sweetness. It matters that even though Pete’s failure to board the train is what drags them all down, it’s Delmar who apologizes to Everett.)

After the encounter with the sirens, we see Delmar splayed on the rocks. We see Everett splayed on the rocks. We see Pete’s clothes splayed on the rocks—but no Pete.

“Of course it’s Pete. Look at him.”

This last one merits special mention, because its effectiveness flows from the Coen brothers’ world-building proficiency.

The question at the core of O Brother is a classic one: is there magic on earth? Everett, fast-talking and cocksure, represents rationality; and Pete and Delmar, principled and less eloquent, represent spirituality.

At the point when the boys meet up with the sirens, Everett’s belief in anything even remotely spiritual-adjacent has gone only as far as is convenient for his narrative: when Pete and Delmar probe Everett about the blind prophet, Everett is quick to explain the theory that blind people are “reputed” to have other extra-sensory powers. As soon as Pete pushes back and reminds Everett that “he said we wouldn’t get the treasure we seek,” though, Everett returns to form: “What the hell does he know? He’s an ignorant old man!”

The denouement’s flood eventually provides a very unsubtle answer to the core question.

Everett is correct, of course, that there is a perfectly logical explanation behind the timing of the flood. Though Everett lies about his motives—the film’s best reversal, one that arrives confidently deep in Act II, is his confession that “there ain’t no treasure”—he wasn’t lying about the time lock; early in the film, both the viewer and Pete and Delmar know they’ve “got but four days” to get to Everett’s house.

And yet he glosses over the fact that, according to any reasonable analysis, he and the boys were in the clutches of “Satan hisself,” a white man with “empty eyes and a big, hollow voice,” who travels around with “a mean old hound dog.” We have seen this Satanic figure with literal fire in his eyes—well, his dark sunglasses—multiple times. (Shout out to my 11-year-old guy Hobbs, who saw this film for the first time recently, and needed only the barn fire shot and Tommy’s description to correctly identify this character.) And, as is to dispel any doubt, he scoffs at Everett’s reliance on the law to save them from execution, looking to the sky and reminding him that “law is a human institution.”

But even though Everett memory-holes those crucial details, even he pauses when he sees the long-predicted “cow on the roof of a cotton house.” Keeping itself, as Everett would say, “unaffiliated” to any particular ideology, the film nevertheless makes plain that there are some events that transcend reason and logic. Magic may, in fact, exist.

That’s admittedly a big wind-up to explain what is so impressive about the siren aftermath. The point is that what makes that scene effective is that the viewer can believe that Pete has indeed been turned into a “horny toad.” For the viewers to be able to take that path, the Coen brothers have to deftly create an ethereal air that permeates the film. (Perhaps my favorite example here is the haunting and beautiful baptism scene.) Everett’s hedging response to Delmar’s suggestion that they need to find a wizard—“I’m not sure that’s Pete”—speaks directly to the needle the Coen brothers have been threading.

Because of what the viewer has seen, they do not have to suspend their belief any further to buy that a wizard just might be the answer to the boys’ problems. Thus, because of their confident and skillful world-building execution, the Coen brothers present Big Dan Teague’s toad-squishing as the most gut-wrenching moment in the film. Indeed, in a show of sympathy to the viewer, the very next scene features a demonstrably unsquished Pete squealing. It’s a very fun set of reversals: The good news is, Pete’s not squished. But then the bad news is, he’s about to be hanged. But then, the good news is, he’s not going to get hanged. But then, the bad news is, he must have given something up to his captors in order to avoid hanging.

I’ll close this thread by saying that in some ways, being a Coen brothers fan could make you more likely to believe in Pete’s toad transition. One of the hallmarks of the Coen brothers’ good movies is that on occasion, they can be absolutely merciless to their characters. I won’t spoil anything here, but this pattern is what helps make Fargo, Burn After Reading, No Country for Old Men, and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs so good.

“We ain’t one-at-a-timin’ here! We’re mass communication’!”

I really enjoyed teaching O Brother, Where Art Thou?. And I think it was the right call to move on from it when I did. I do see myself potentially teaching it again. If and when I do, I want to add emphasis to the thematic implications of the gubernatorial race subplot; I think it would be a fun challenge to discuss the campaigns of Pappy O’Daniel and Homer Stokes, especially through the lens of current politics. I would also want to put emphasis on the film’s real star: the music. The soundtrack was a sensation, holds up today, and is an elite example of tying music to filmmaker agenda.

“You don’t say much, friend, but when you do, it’s to the point, and I salute you for it.”

See you on February 7th, when we discuss Barbie (2023).